Exercise 3.0: Evolutionary Design of κ3-Chelator for Pt(CO)

Introduction

Multidentate ligands play a critical role in transition-metal chemistry. Therefore, this exercise is dedicated to the design of rings that involve a metal center and a tuneable organic ligand.

Like in the previous exercise we set as chemical goal the elongation of the CO bond on Pt(II) complexes. This time, however, we explore tridentate ligands that adhere to the previous [X, L, X] pattern, namely, so that the L site is trans to the carbonyl ligand and the two X sites are both cis to CO and trans to each other.

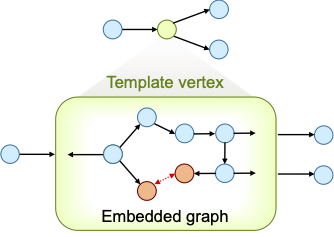

To define such constrain, while allowing DENOPTIM to change the components forming the ring, we make use of a special type of vertex called Template. Templates are vertices that can embed graphs and can define constraints on such embedded graphs. Also, while the embedded graph may be editable, the Template appears as a single vertex, when seen from the outside.

Figure 1: A template vertex contains an embedded graph (bottom), but is seen as a single vertex in the graph that owns the template vertex (top).

Compared to the design of monodentate ligands, the design of multidentate, as the design of rings in general, poses an additional challenge: the closability of a chain cannot be given for granted unless the chain elements are constrained to include only known rings. Even then, substituents on the chain may prevent the actual formation of the ring by adding steric hindrance, or by adding additional constraints (e.g., fused rings). Since in de novo design we typically want to explore unknown structural features, we want i) to avoid assumptions on the closability and ii) to assess closability on the fly. In this example, we use a hybrid approach in that only rings with a certain size (i.e., atom count) are allowed to form, but their closability is evaluated only in the molecular modeling workflow by a dedicated ring-closing conformational search (further details at J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 9, 1844–1856).

Within DENOPTIM’s graph representation rings are created involving a pairs of special vertexes (orange in Figure 1): the so-called ring-closing vertexes, or RCVs. The RCVs have two roles: First, they represent the possibility to form a chord which is created only once a pair of RCVs commits to this purpose. Second, they contain dummy atoms (i.e., the ring closing attractors) that are used in the ring-closing conformational search to fold open chains into a ring-closing conformation. Such conformation brings the head and tail of the chain in relative positions that allow formation of a bond between them, thus closing the open chain into a ring (see J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 9, 1844–1856).

Again, to save time, we will use a list of pre-computed molecules that has been processed via the ring-closing conformational search and geometry optimisation workflow as to compute the fitness value (i.e., the length of the C≡O bond). Therefore, the ring-closing conformational search, as well as actual molecular modeling task, will not take place during this exercise.

Instructions

Creation of a Template Vertex

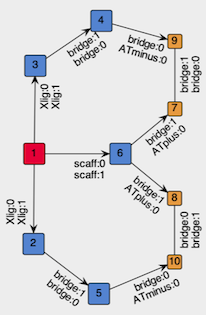

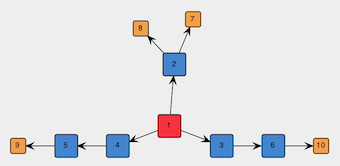

To create the Template vertex for our tridentate skeleton, we build the graph that will be embedded in the template and then we wrap-it into a vertex. The graph to embed should contain the metal center (red in Figure 2) and place-holding vertexes for the components of the chelation system: the coordinating sites, and the bridges (both blue in Figure 2). In addition, to require formation of the rings, we include in the template two pairs of ring-closing vertexes (orange in Figure 2).

Figure 2: Structure of the graph to be embedded in the template vertex.

Start DENOPTIM from within the

exercise_3.0folder. This is done from the Terminal (macOS/Linux) or the Anaconda prompt (Windows):

cd your_path_to_exercise_3.0

denoptim

Choose the shortcut to

Make GraphsorFile->New->New Graphsto open the graph editor.Since we are going to build a graph that is meant for a specific space of building blocks, we load such space to make the building blocks available. Click on the

Load BBSpacebutton on the right-hand part of the editor. ChooseUse parameters from an existing fileand browse to load filemonodentate_BBSpace.par, which is contained in theexercise_3.0folder. Once the parameters imported from the file are displayed, click onCreate BB Space.Start the construction of a new graph by clicking on

Addbutton on the top-right. Chose toBuilda graph starting from a building block of typeScaffold. There is only one such vertex, and is the Pt-CO fragment we have already used in the previous exercise. Select that vertex to use it as the seed of our graph.

Note On the visual representation of the graph can select vertexes by clicking on them to visualise their content (if any). Right-clicking on the graph visualisation panel offers additional functionality including the refinement of the graph arrangement, and the displaying of features of vertices, edges, and attachment points.

Note: DENOPTIM’s graph representation have no dimensionality. Therefore, the relative placement of vertexes and attachment points is completely irrelevant. You can drag any component of the graph to help visualisation. Yet, such changes affect only on the graphical depiction and have no effect on the graph representation itself.

Visualise the content of the only vertex in the graph by clicking on it. Then, click on the yellow dot to select the attachment point corresponding to the coordination site trans to CO.

Click on the button

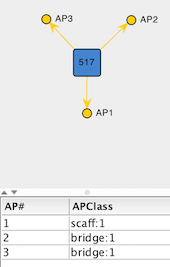

Add Empty Vertexto add a placeholder for the L-type site of the ligand. This opens a dialog that allows creation of a new vertex by defining the list of attachment points. In this case, add three attachment points via theAdd APbutton: one with APClassscaff:1and two with APClassbridge:1.Make sure the drop-down menu located below the list of attachment points selects

FRAGMENTas type of building block, and clickCreate. The result should be similar to the figure below.

Figure 3: Empty Vertex created to represent the L-type site on the tridentate ligand template.

In the list of attachment points, click on the row with APClass

scaff:1to specify which attachment point should be the one used to append this empty vertex onto the attachment point that was selected on the graph. Clicking onConfirm selected APtriggers the addition of the vertex to the graph and the formation of the corresponding edge.

Note: the new vertex is depicted in a random position. Right-click and

Refine node locationsto improve the graphical depiction of the graph.

The procedure for appending a single empty vertex can now be repeated on the other two APs on the Pt-CO vertex, those with

Xlig:0APClass. Since these two parts of the graph are equivalent in Figure 2, you can select both APs to append a copy of the created vertex on each of them. do this twice:

first, to add an empty vertex with APs

Xlig:1andbridge:1then, to append an empty vertex with two APs

bridge:0

To add RCVs (orange in Figure 2), instead, we use fragments saved in the library that defined the space of building blocks. To this end, select the two APs on the first empty vertex you have added (i.e., the one representing the L-type site), click

Add Vertex from BB Spaceand choseAny Vertex. Choose the second-last vertex, i.e., the one with a single AP of classATplus:0, and append them to the graph.Repeat for the two last attachment points, but this time choose the very last vertex, i.e., the one with a single AP of class

ATminus:0. The result should be similar to the following picture:

Figure 4: Spanning tree of the graph to be embedded in the template.

The above graph is symmetric but there is nothing preventing place-holder vertexes such as 3 and 4 in Figure 4 (NB: the vertex identifiers may differ in your graph) to be replaced by different actual vertexes, thus leading to an asymmetric graph. One may be interested in both symmetric and asymmetric graphs, but ins this exercise we want only symmetric graphs. Therefore, we select sets of vertexes that are supposed to be symmetric (e.g., in Figure 4, the two sets [3, 4] and [5, 6]) and click on

Set as Symmetric.

Note after selecting a vertex, do shift-click on another vertex to expand the selection.

Question 1 what is the effect of symmetric constrains on the number of candidate graphs that can be built from the graph in Figure 4?

The graph in Figure 4 is still acyclic, so we add the chords between the appropriate pairs of RCVs by selecting a pair and clicking on

Add Chord.The graph is now complete. Drag-click to select all vertexes, right-click and choose

Show APClasses. Verify the result by comparison with Figure 2. Click onSave changesand look at eh content on the molecular representation in the bottom-left part of the screen. The system contains only the atoms from the Pt-CO fragment and the dummy atoms coming from the RCVs.So far, the graph is special only in the fact that it contains empty vertexes. More importantly, it is not yet embedded in a template. To enclose the graph in a template, click on

Save Library of Templatesand choose Contract:FIXED_STRUCTand Type:SCAFFOLD. Save aslib_scaffolds_my_template.sdfunder theexercise_3.0folder.

Evolutionary Design with Templates

We are now going to use the template vertex we have just created to design our symmetric chelates for Pt-CO complexes.

Open the file of parameters

denoptim input_parameters

and inspect the parameters. This file assumes you have created the lib_scaffolds_my_template.sdf file in the previous part of the exercise.

Run the evolutionary design by clicking on

Run Now....

Note: giving a file with input parameters the evolutionary design can be started directly from the command line:

denoptim -r GA input_parameters

Once the experiment is finished, open the output with

File->Open Recent...and inspect the results.

Note: opening the GA inspector is also among the operations that can be done directly from the command line:

denoptim <pathname_to_folder_RUNYYYYMMDDHHMMSS>

Question 2: Consider the symmetry of the generated complexes. Search for ligands that have lower symmetry than others, for example, N-heterocyclic carbenes with different sets of substituents on the carbon atoms of their backbone. Is the graph representation symmetric? Motivate your answer reflecting on DENOPTIM’s definition of symmetric attachment points.

Question 3: plot the number of attempts to build new candidates. How does it compare with the design of ligand sets made only of monodentate ligands? Explain the difference.

Discussion

Consider a catalyst of your choice that has a multidentate ligand. Build a template vertex that would allow to re-design the chelating ligand. Describe your reasoning and show the template’s embedded graph in your report. If needed, describe also what fragment you would need to generate to address the specific chemistry of your catalyst.